The conversation has as its aspiration to think through the stakes of what it means to engage the concept of “possess/ing” in the context of what we collectively refer to as ethnographic and/or world museums. We enter into this conversation with four explicit—and seemingly, at best remotely related—intertexts:

- First, what Nicholas Thomas notes is a “sense of urgency around art and empire […] driven most conspicuously by student and activist campaigning for the ‘decolonization’ of curricula, universities, public culture and representations of heritage and history” (15).

- Second, this above inquiry is itself at once undergirded by and rendered concrete in the crucial question of ownership of those actual “objects” that constitute the vast collections of our museums, what the project Pressing Matter: Ownership, Value, and the Question of Colonial Heritage in Museums describes as the “debates” around the “growing contestation over what to do with colonial heritage held in museums [which] reveals polarized positions.”

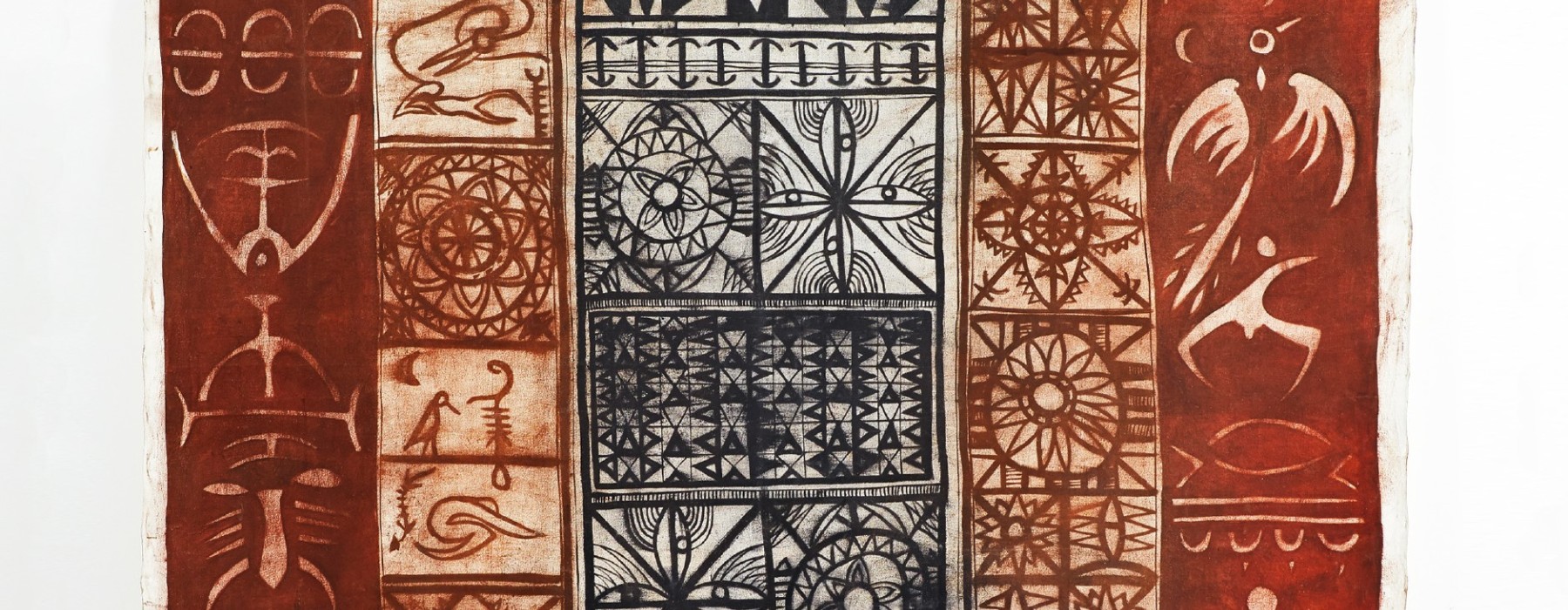

- Third, the theory and scholarship around the lexical intendant other of possession—that is “dispossession,” which constitutes the title of a chapter in Nicholas Thomas’s book: “Landscapes: Possession and Dispossession.” That is, what does it mean to think questions of environmental degradation, (non)sovereignty, or even the very notion of the aesthetic without noting how our present world is predicated on the systematic dispossession of those globally understood as less privileged and/or belonging to a Global South/Global Majority on the part of those with European and Europeanly-informed privilege? And how does possession as a concept of extraction, but also of being-self-through-each-other trouble our dichotomous conceptions of who is victim and who is perpetrator, as per Michael Rothberg?1

- Fourth, how do our museums staunchly remain wedded to the canonically defined disciplines that make it difficult to create fluidity among the categories of art, ethnography, nature, and history, which continue to order not just the world’s humans, but also the world’s species and materials into rigid civilizationally conceived hierarchies of being?

- And finally, the contested question of what it means to be possessed—the European word, often understood as degrading2—and used to designate an entire philosophy of “the universe,” which in the words of Souleymane Bachir Diagne allow to “open up ourselves to the object, the art object in particular, by means of a rhythmic attitude that puts us on the same wavelength with it.”3