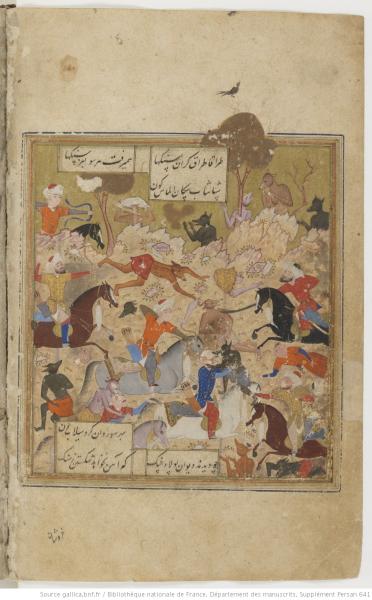

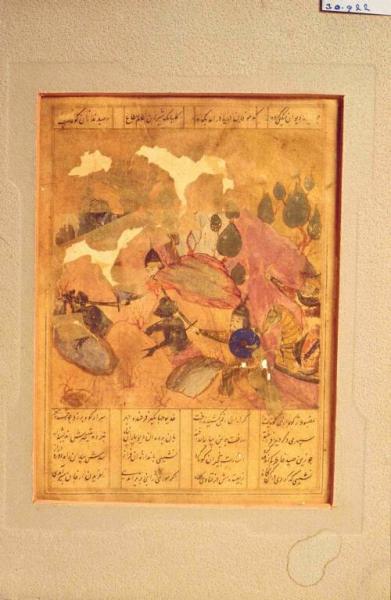

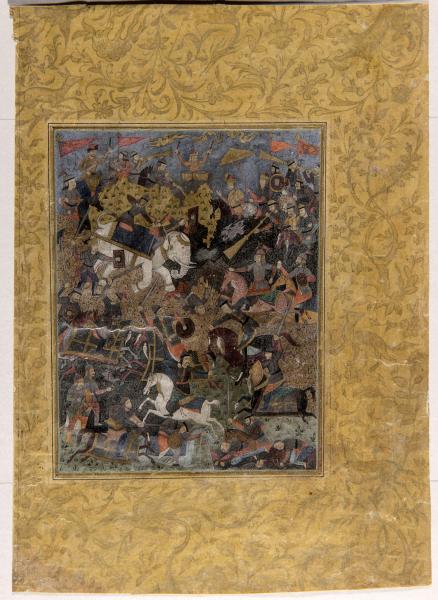

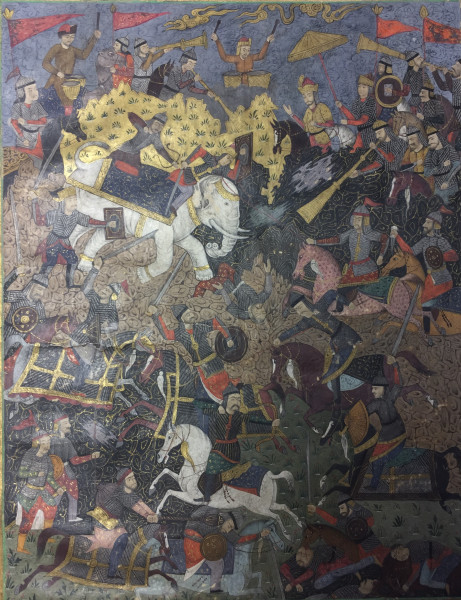

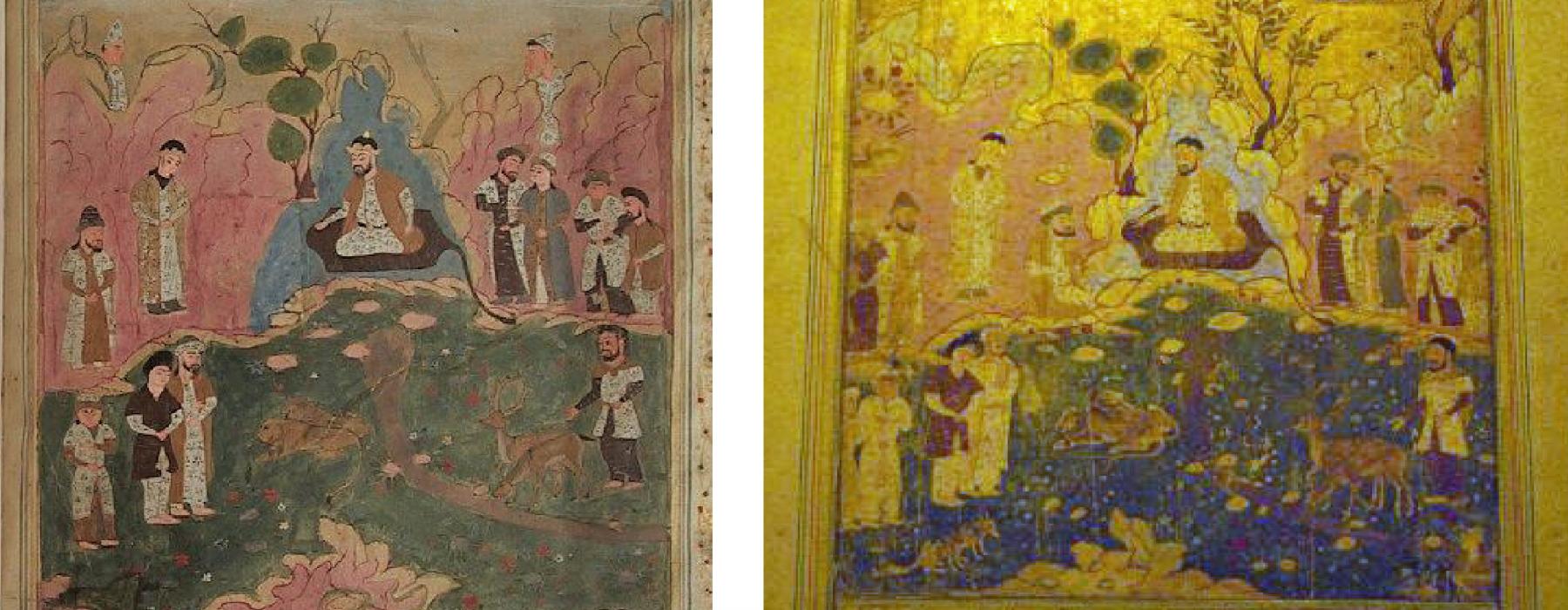

Like many other collections, the National Museum of World Cultures contains several specimens of illustrations and lacquered book covers, with pages derived from manuscripts mounted on beautiful illuminated papers that belie the violence of their having been torn from original bound books and albums. Looking through the online catalogue, I noticed that these disembodied objects were often given the accompanying provenance in the museum database: “Southwest and Central Asia/ Southwest Asia/ Iran, about 16th—17th centuries.” This two-century margin covers such geographical and chronological breadth that it is essentially useless to the informed specialist and member of the general public alike. What is more, in the act of classification or object identification there is a very big difference in approaching loose pages as opposed to intact manuscripts. What links the disassembled to the bound is a careful analysis of the illustrations and the subtleties of the styles used to render them. The art historian George Kubler declares, “Style pertains to the consideration of static groups of entities. It vanishes once these entities are restored to the flow of time.”[2] So too can static pages be restored to their original flow when one visualizes their insertion into complete manuscripts from which they came.

Classificatory schemes for book arts coming from present-day Azerbaijan, Armenia, Turkey, Iran, India, Pakistan, and Central Asia (implying Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Afghanistan) between the 11th-19th centuries were put in place in the early-twentieth century. They culminated in a chart created by the British scholar B.W. Robinson in 1967 (fig. 1). In it, we see an arrangement based horizontally by time period (half-centuries), and vertically by columns of individual cities (Baghdad, Tabriz, Qazvin, etc), and with broader groupings of dynastic names (Mongol, Timurid, Safawid, etc) to further divide up the periods. Taking the city of Shiraz as an example, with this diagram we can move vertically to see changes in rulership across the centuries and the many dynasties ruling over it (such as Injuid, Muzaffarid, Timurid, Turkman, Safavid, and Zand overlords). We can move horizontally focusing on the period 1500-1550: a rich epoch witnessing the waning of the Turkmans and Timurids early on, the rise of the Safavids, and their rivals in Central Asia based in Samarqand and Bukhara.