These were photographs that emphasised the spectacularity of volcanic eruptions. Where the images were of more ‘placidly’ active volcanoes––the picturesque smoking crater––they emphasised colonial notions of tropicality. From the late nineteenth century onwards, a grislier genre of photography emerged, documenting the human toll of disasters, including razed villages, the dead and wounded, and refugees. These were the photographs I had in mind for examining when I began my project on ‘Disaster, human suffering and colonial photography’; and indeed, they will have an important place in my research. But as I began working through the archives, I had to acknowledge how frequently European photographers were drawn to volatile tropical landscapes, such as volcano sites, which only sometimes turned disastrous. It made me think about how nineteenth and twentieth-century Indonesians were living with disaster as a constant possibility, but one integrated into the everyday in ways that warranted closer inspection.

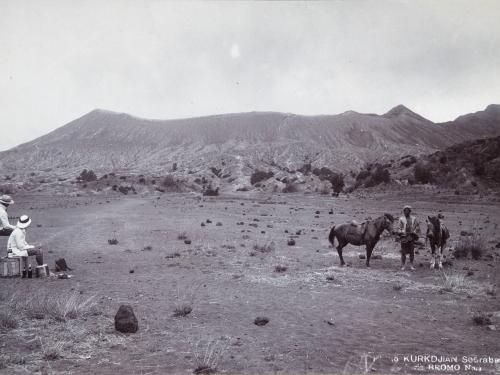

As Liesbeth Ouwehand has suggested1, commercial photographers stimulated European tourism to volcano sites in colonial Indonesia. In my research I have discovered just how important photography was for volcano enthusiasts, who often combined a hobby interest in the emerging science of geology and volcanology with motor tours of Java to ‘hill stations’ in volcanic mountain ranges. Such tours typically involved with nice hotels, guided tours and hiking parties. Indeed, the most popular and frequently photographed destinations on Java were Gunung Papandayan, accessible from the resort town of Garut, and Bromo, Smeru and Batok in the Tengger Ranges.

Commercial photographs from the 1890s and 1900s had an important afterlife for decades after their making, well into the era of amateur photography, which seriously took off in the 1920s. In many albums that I looked at, volcano enthusiasts collected ‘old’ commercial photographs and mingled them together with their own, self-made snapshots of the same locations. Sometimes the two kinds of photographs were even laid side by side, as though the album-maker was recording a goal achieved: with the (commercial) photograph that inspired her to seek out the volcano in the first place next to the snapshot of the summit (or the crater) taken by her own hand beside it. These practices show that commercial photographs made in the age of tripods and brittle plates were placed in interaction with those of amateurs using hand-held cameras and roll films. Changes in technology did not therefore displace the circulation of older images. On the contrary, earlier commercial photographs became iconic as references for amateur photographers.

The social function of volcano photographs, old and new, was thus to inspire but also document journeys that European travellers were making through colonial Indonesia’s picturesque, spectacular and volatile landscapes. The modes in which Europeans interacted with Indonesia’s environment, as tourists and adventurers, was shaped by photography.

Two of the endlessly repeated themes in the volcano photographs I examined in my research were, first, the close-up of the smoking crater and second, the panoramic view of taken from the peak of another mountain.