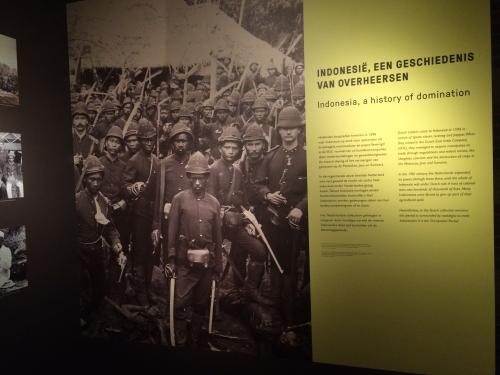

The alcove display, ‘Indonesia, a history of domination’ (pictured above), is one example of that intervention. It discusses the theme of colonial violence, illustrated by a photograph taken during the Dutch conquest of Aceh in the late nineteenth century. The armed soldiers of the KNIL (Koninklijk Nederlandsch-Indisch Leger, colonial army) take up most of the space in this image. On the ground at their feet, one can just make out the bodies of their victims.

The wall-print is actually a cropped version of the original photograph held in the Tropenmuseum archives. The original gives almost equal space to the dead on the ground. Why has the museum edited the photograph this way for display, to ostensibly focus on the perpetrators of violence and minimize the Acehnese who died at the ends of bayonets? Is this an instance of sensitivity, or censorship?

Late last year, I talked to Pim Westerkamp, the NMVW’s Curator for Southeast Asia, about this new display. Pim said that it was his decision to introduce the photograph to the exhibition, with the aim of addressing the complex topic of colonial violence and Indonesian resistance. The exhibition-makers––who comprise a specialist department responsible for the staging of exhibitions, and who work in consultation with but by no means at the direction of curators––disagreed with the choice. They argued that the representation of slaughtered Acehnese was too explicit for such an exhibition space (which is frequently visited by children and school groups). The compromise was to crop the photograph and omit the faces of the dead.

I am still thinking about this image, the processes that have shaped its ‘social life’ (following Kopytoff and Appadurai) in the museum, and the question of sensitivities to and censorship of colonial violence.

In my own research on natural disasters, war and conflict in colonial Indonesia, from the invention of photography to decolonization (c. 1839–1950), I used the NMVW’s database (the ‘TMS’) to compile a dataset, or working archive, of hundreds of photographs showing Indonesians at the centre of both kinds of disaster. In the TMS I sometimes encountered the following annotation, left by a registrar or curator or some other museum employee who worked on the database: ‘not for the public – human remains’. Indeed, many of these photographs catalogued in the TMS have not had an audience for a long time: the NMVW’s public, searchable database of objects shows only a portion of what is listed on the TMS, and the museums’ exhibitions necessarily make very limited use of the tens of thousands of photographs in the collections.

The note, ‘not for the public – human remains’, strikes me as the first link in a long chain of acts by museum workers, beginning with data-entry and ending in decisions about display, that inform the complex issue of what the public knows about histories of colonial disaster, whose perspectives those histories are narrated from, and the ethics of spectatorship.

These are high-stakes issues in media coverage of contemporary disasters, as well as in public discussions about the vivid legacies of colonialism in contemporary life in the Netherlands, Indonesia and, indeed, wherever empire is ongoing or a recent memory. Every scholar working on colonialism and photography has to work through the ethics of this context when deciding how to analyse and reproduce images in their research. I’ve had to engage directly with this problematic in my own recent work on Dutch soldiers’ amateur photographs taken during the military operations launched by the Netherlands in response to the Indonesian declaration of independence (see a clip of one of the talks I have given on this topic here).1

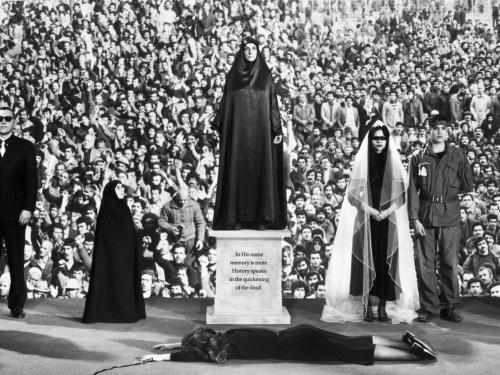

Photographs of atrocities committed during colonial wars can serve as evidence of disputed incidents, in cases working towards truth, justice and reconciliation, as well as for compensation and restitution. Significantly, however, arguments about ‘evidence’ are often more important for convincing the community from which the perpetrators of violence came. Victims and survivors already know what happened, and for them, equally important is the question of how to represent images of suffering in their community in ways that balance truth and testimony, on the one hand, with dignity, care and agency on the other.

These are considerations that are increasingly given to photographs of suffering people under armed occupation, colonialism, and slavery, and which might perhaps be extended to images of suffering in natural disaster, certainly where the visual economy in which they first circulated was a colonial one. Or so I’ve been thinking, as I research disaster in Indonesia over the first century of photography.

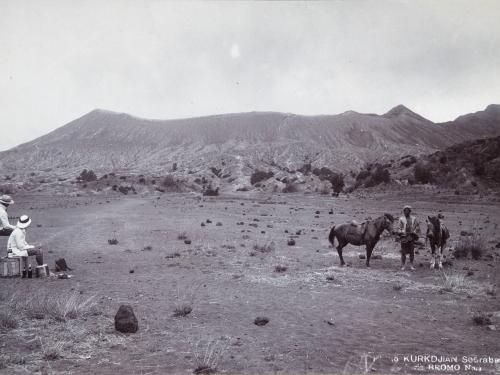

From the turn of the century, as Liesbeth Ouwehand has been the first to chart,2 commercial photographers in Indonesia began recording the victims of disaster as they died during volcanic eruptions or in earthquakes. The photographs taken in the aftermath of the 1898 Ambon earthquake are an early example. Similar photographs by commercial photographers exist in several Dutch archives, which suggests a market existed for them, and what we are seeing here is the origins of disaster tourism. In the decades to follow, increasingly explicit photographs were captured not only by commercial photographers, but also by bystanders who produced amateur photographs of local disasters, and who mingled the two genres in their own collections.