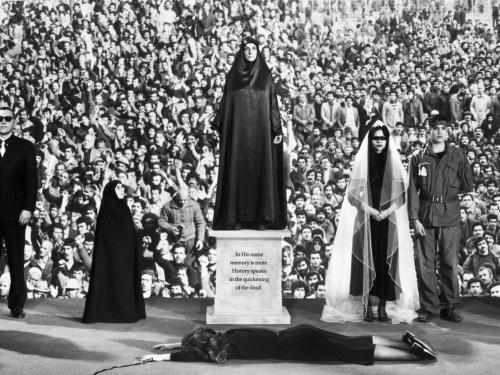

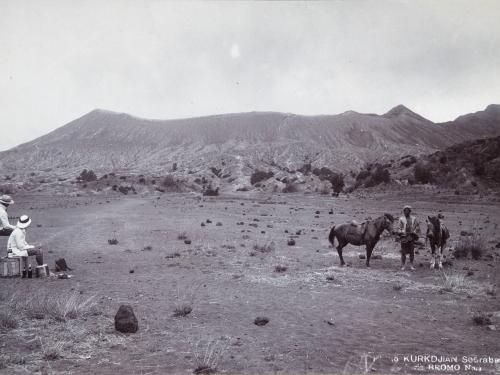

The composition of the photograph encourages us to adopt a certain perspective. The three Dutch figures have their backs to us, and because we cannot see their faces (which is unusual in an amateur portrait) we want to know what they are looking at. We can see what has caught their attention: the billowing cloud of volcanic ash and smoke. We can also see what the photographer standing behind them saw: the whites of their clothes and shoes mirror, and lead the viewer’s eye to, the bright plume in the centre. Blending into the dark contrast of the volcano’s rim stand two Indonesian porters and a pony. They occupy the same foreground as the Dutch spectators, and are the same resolution as the other elements of the photograph, but they remain somehow less visible – cast into shadow, not looking at us, not looking at the volcano.

I wondered, why are there so many books on volcanology and volcano tourism in Dutch colonial library collections, but these Indonesian porters and guides are not mentioned in those texts? Why have I never noticed these men before? How can I find out more about them?

The arrangement of the 1954 photograph at Bromo, which privileges colonial gazes, might be viewed as a metaphor for histories of colonial disaster photography, or perhaps more generally, for recurring interpretive frameworks in histories of colonial photography. Since the photograph was taken by a Dutch person in Indonesia, and it is in a colonial archive (although it was taken four years after Indonesia won its independence), we want to focus on how the image reproduces colonial perspectives, which are inherently based in the unequal, imperial exercise of rights to power, as per Ariella Azoulay in her 2018 Gerbrands Lecture.

Such a dynamic certainly inflects this album and the specific archive that holds it, but it is by no means the only interpretation of either. Historians of colonialism and postcolonial theorists of photography such as Christopher Pinney, Elizabeth Edwards, and Jane Lydon, to name just a few, have long argued that it can paradoxically revive and enhance (neo-)colonial power to interpret photographs in only this way, without regard for how they may sit within present and historic Indigenous communities of subjects and spectators. It takes the framing of new questions––drawn from historical case studies, from Indigenous activism, and from a range of theoretical and methodological approaches to colonial sources––to see empirical evidence for alternative stories and perspectives in such photographs.

I was at the Research Center for Material Culture (RCMC) to do precisely that: to work on a large project, generously supported by the RCMC as well as the Australian Research Council, titled ‘Disaster, Human Suffering and Colonial Photography’. My project seeks to understand Indonesian experiences of disaster, as represented in photography over the first century of photography, a period that coincides with the last century of Dutch rule in Indonesia.

As is so often the case when you get away from planning at the screen and actually go to the archives (or the field, or wherever your discipline demands that you go), my research focus shifted when I got here and began working with the sources themselves. I started out thinking I was going to be concentrating on the acute phase of disasters, where all the suffering was (like my project title says). But then I discovered that what was far more interesting, and maybe even more important, was the question of how photography helps us understand how Indonesians ‘live’ with disaster over the longer term.

I should have thought of this sooner, because I have for years been reading and teaching an interdisciplinary scholarship that discusses both environmental catastrophe and war and conflict as processes, where the acute phase is preceded by social factors that condition vulnerabilities to disaster. These same factors––in my discipline, you’d call them historical and cultural context––also shape individual and community recovery, reconstruction, peace, justice and reconciliation; who gets to claim victim status, who is a ‘hero’, whose experiences form the master narrative of how particular disasters are remembered or forgotten.

For Indonesia, this is an especially relevant framework because it is an archipelago on the Pacific Ring of Fire. Volcanoes, earthquakes and floods have shaped its human and ecological history. In addition, Indonesia has just emerged from a violent, contested twentieth century, one shaped by colonial conquest, civil and anti-colonial war, purges and mass violence. For Indonesia, these two contexts suggest that suffering and disaster are not only recent, but imminent. How people remain resilient, and the uses they make of disastrous pasts in the present, are crucial to telling the story of living with disaster – just as much as understanding the ways in which lives and communities are destroyed at the acute stages of the disaster.

This blog, which will come in three parts, reflects partway through my archival research on what I have found and been thinking on this topic about so far.

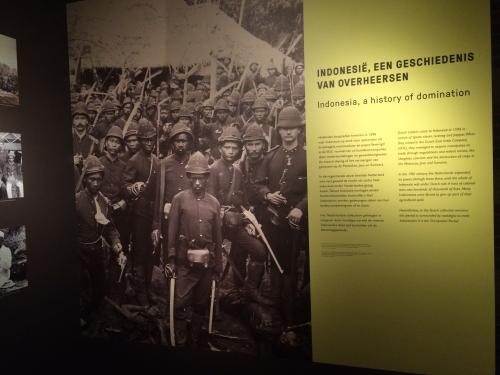

My project examines Indonesians at the centre of both environmental disasters and war and conflict, from roughly the invention of photography (1839) to the end of Dutch rule (1950). It is an important ‘long century’, because in this period the borders and constituents of the Netherlands East Indies were expanded and consolidated by the Dutch through a series of military conflicts. And for the first time, Indonesia’s frequent natural disasters were captured through the new medium of photography, which quickly proliferated across the archipelago, not just at the sites where it was practiced, but also in the different functions and audiences it grew to serve. In the beginning (1840s–70s), photography was used in Indonesia for archaeological research, scientific and ethnographic expeditions, and military purposes, but these functions expanded and overlapped with consumer uses like commercial and studio photography, postcards and commissioned albums (1860s–1910). Amateur photography really took off in the 1920s, as did the use of photographs and photographic techniques to illustrate colonial newspapers, printed books and journals.

It is methodologically challenging to examine together two types of disasters that are usually treated separately by historians and many other scholars in the humanities, who instead commonly specialize in the one area or the other. As a historian of photography, I have noticed that, by the mid-twentieth century, it is often difficult to distinguish what kind of disaster we are looking at based on the image alone. Particular tropes that we are now very familiar with––like that of the suffering child–– appear to have emerged less than a hundred years ago. Journalists, documentary photographers, and charity and aid organizations frequently use images of suffering children to signal a humanitarian crisis. But such images have a genealogy that needs to be better understood, in part so that we can answer the pressing questions: what is our responsibility as spectators of other people’s suffering, and what are the ethics of looking at disaster?

The rise of social media makes these queries urgent, as seen recently with the obstructive and insensitive ‘selfie’ tourism in Indonesia following the 2018 tsunami in the Sunda Strait (see, for example, articles in The Guardian and The Conversation). At the same time, questions around the ethics of spectatorship have been with us since at least Susan Sontag’s famous essay, Regarding the Pain of Others (2003). These concerns are amplified when we consider colonial archives, where the context in which photographs were made was one of imperial encounter.

What, then, are the limits and possibilities for understanding historical Indonesian experiences of disaster in a colonial context, and often, in photographs that were made by Europeans?

This is a big project (and getting bigger all the time, to my dismay), one that requires extensive archival research and the creation of a ‘dataset’, if such a term can be used, of photographs from the period in question. I also need to gather a rich context of related documentary archives that situate these photographs in their visual economies and cultures, past and present. I began constructing the dataset for natural disasters, and digging into the larger network of archives, in 2018, in archives that include (but have not been limited to) those of the Dutch Nationaal Museum van Wereldculturen (NMVW), particularly the Tropenmuseum (Amsterdam) and the Volkenkunde Museum (Leiden). Pim Westerkamp (Curator Southeast Asia), Ingeborg Eggink (Registrar Photograph Collections), and Liesbeth Ouwehand (Curator Photography) were all involved in helping me digitally locate and then access the originals of the objects I needed in the vast NMVW collections.

I have looked at every original I could get my hands on, and not only because not all the items are catalogued online (although the NMVW has an impressive searchable database). As a historian, my discipline demands that I be able to reconstruct the context of the photograph, and follow clues for chasing up related archives, which I cannot do unless I can see how photographs were used, circulated, distributed, and responded to. Nineteenth and twentieth-century photographs are objects, and their handmade settings typically bear traces of these meanings and movements. I have seen no online database yet, no matter how sophisticated, that can translate all these details adequately to tags and search terms.

Attending to the long ‘social life of things’, as Igor Kopytoff and Arjun Appadurai established in the 1980s, is therefore part of my practice as a historian of photography. I cannot do that job properly without also examining how photograph collections connect to other items in archive and museum collections, historical and contemporary. My concerns intersect with other stakeholders. The materiality of museum collections is a key concern of museum specialists––from curators and conservators to exhibition makers––and most importantly, their audiences, and it is museum practices that shape collections. Importantly, the materiality of photographs was also the most important thing for the people who made them in the first place, for their audiences and communities.

I am interested in how photo-objects might yet be curated to tell stories about Indonesians living with disaster, in the present and future. As a historian, I am therefore invested not just in discovering new primary sources and writing new interpretations of the past, but also in addressing methodological questions in history and photo theory, including epistemological ones such as how it is that we can know what we (think) we know with photographs. I want to extend my research to thinking about how museums might narrate or curate some of the material I’ve been thinking with. The next part in this blog series will start to do just that.